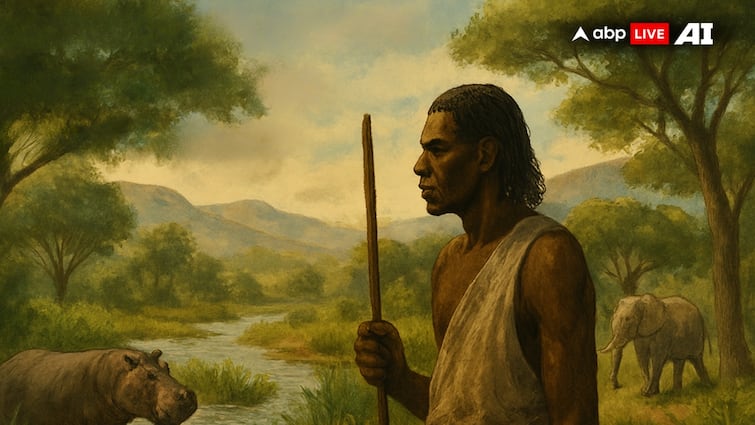

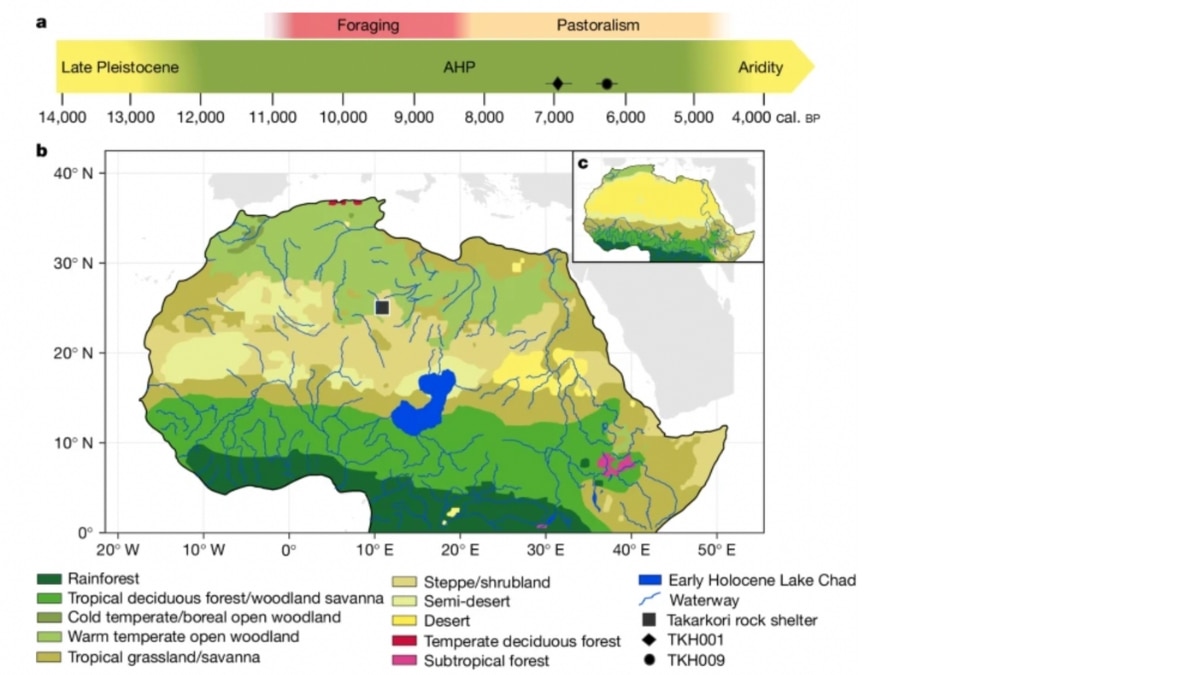

Now a vast and parched expanse of sand and stone, the Sahara Desert hides secrets of a time when it teemed with life. Between 14,500 and 5,000 years ago, this inhospitable region was a lush savannah, threaded with rivers, dotted with lakes, and alive with people, animals, and forests. Scientists call this era the African Humid Period (AHP). Until recently, little was known about the people who lived there.

However, now, with the successful recovery and analysis of ancient DNA from 7,000-year-old mummified remains, researchers have reconstructed the genetic profile of a previously unknown population that once thrived in the heart of the Sahara.

The analysis, published in Nature journal earlier this month, challenges previous assumptions that the Green Sahara served as a migration corridor between northern and sub-Saharan Africa.

“The green Sahara wasn’t a corridor for the movement of people, but for sure it was a corridor for ideas and technology,” Savino di Lernia, co-author of the study who teaches African archaeology and ethnoarchaeology at Rome’s Sapienza University, was quoted as saying in Science.

This is the first time scientists have been able to recover and sequence full human genomes from remains buried in such an extreme desert climate.

A Genetic Time Capsule From Takarkori

According to the study published in Nature, archaeologists uncovered at the Takarkori rock shelter in southwestern Libya’s Tadrart Acacus Mountains two naturally mummified women buried around 7,000 years ago. DNA analysis reveals that these women belonged to a deeply rooted North African lineage that diverged from other human populations before the major out-of-Africa expansions. Their genome shows strong continuity with 15,000-year-old hunter-gatherers from Taforalt Cave in Morocco, confirming a long-standing, stable population in the region.

Notably, while traces of Neanderthal ancestry are present — suggesting ancient contact with Eurasian populations — the Takarkori genomes are largely unadmixed, with only minimal Levantine gene flow. This finding challenges assumptions that the spread of pastoralism in North Africa was driven by mass migration from the Near East, researchers pointed out in the study.

Technical Breakthroughs In Ancient DNA Recovery

Recovering ancient DNA in hyper-arid environments like the Sahara poses extreme technical challenges due to heat-induced degradation and contamination. In this study, researchers used “hybridization” capture techniques, which selectively enrich ancient human DNA from degraded samples, paired with cutting-edge computational tools to assemble and authenticate the genomes.

Using short-read alignment, damage pattern analysis, and principal component analysis (PCA), scientists confirmed the authenticity of the sequences and positioned the individuals within a broader ancient genetic landscape. These methodological advances open up new possibilities for studying early populations in previously inaccessible climates.

Though this specific Saharan lineage no longer exists in its pure form, genetic analysis confirms that it contributes significantly to modern North African populations. “Their genetic legacy offers a new perspective on the region’s deep history,” according to Johannes Krause, archaeogeneticist from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology who co-authored the study.

Population Structure And Social Resilience

An important insight comes from Runs of Homozygosity (ROH) analysis, which shows an absence of inbreeding in the Takarkori individuals. This strongly suggests they were part of a socially connected, genetically diverse population, contradicting assumptions that desert communities were small and isolated.

Instead, the data point to robust demographic networks and sustained gene flow within Green Sahara societies. Such population resilience likely helped communities adapt to climatic shifts during the African Humid Period, facilitating the spread of pastoralism across a mosaic of ecological zones.

While once lush, the study says, the “Green Sahara” was not a homogenous savannah. Instead, paleoclimatic reconstructions and pollen-based timelines reveal a landscape of fragmented microclimates — lakes, wetlands, and grasslands punctuated by arid zones. This ecological patchwork likely limited long-distance gene flow, even as ideas like animal domestication spread across regions.

“The Sahara, spanning around 9 million km and housing diverse biomes, such as grasslands, wetlands, woodlands, lakes, mountains and savannas, probably saw fragmented habitats impacting human gene flow. These ecological barriers, combined with social and cultural barriers, spatial structuring of populations, and the selective adoption of specific practices, may have facilitated the widespread dissemination of similar archaeological features, while limiting extensive genetic admixture,” the authors note.

Despite the development of mobile pastoralist lifeways, genetic evidence shows limited admixture with Levantine groups, suggesting interaction occurred, but not at levels sufficient to disrupt local ancestries. The Saharan population structure was therefore shaped as much by environmental barriers as by cultural preferences or mobility patterns.

Doonited Affiliated: Syndicate News Hunt

This report has been published as part of an auto-generated syndicated wire feed. Except for the headline, the content has not been modified or edited by Doonited